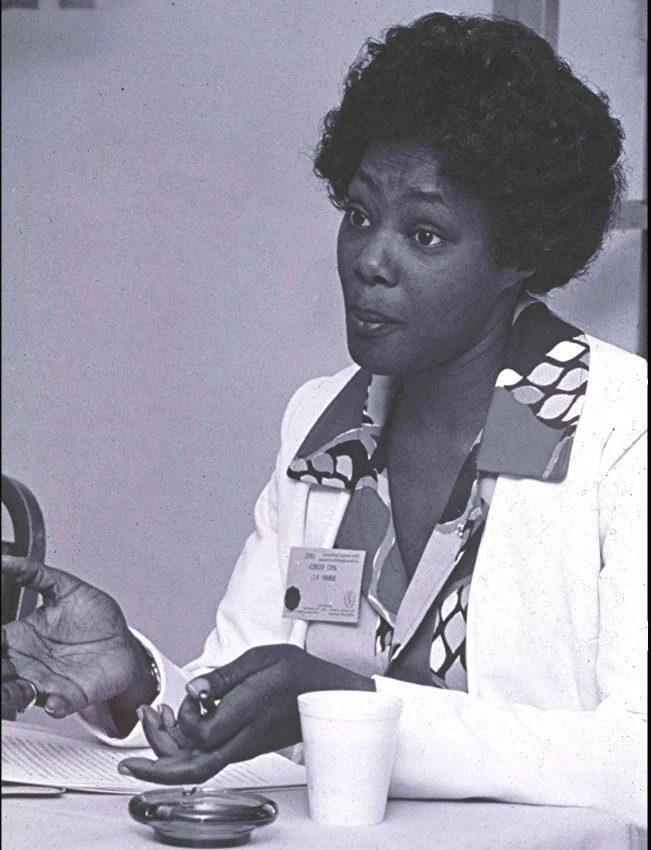

#BlackWomeninBullCity | Joyce Nichols

Hey Friends! What a wonderful week this has been. I'm excited to share a bit about Ms. Joyce Nichols. She was originally from Roxboro, NC, but came to Durham to pursue a degree at what was then called, Carolina College, now known as North Carolina Central University. She was unable to complete her schooling at NCCU due to finances. Nichols later earned a scholarship to study and become a licensed practical nurse at the Durham Technical Institute. She was working at Duke Hospital when she got word of the Physician Assistant program at Duke. Nichols had become well acquainted with ex-corpsmen who would come into the cardiac care unit to work until the fall Physician Assistant's program. The admissions committee was skeptical about admitting her to the program, being that she lacked corpsmen experience and was a mother taking care of a family.

A woman, African American, working-class, a mother, and little money to cover her education…

The odds were against her, but she persisted and won the faculty over and became the first woman to be formally educated as a physician assistant. While it was academically challenging for her, she rose from next to last to be in the top 50% of the class. She became the first PA to be trained in the cardiology subspecialty. Nichols was even elected as the vice president of the class by her all-male class.

Part of her story that made me smile is that she says she owed so much of her gratitude towards her second husband, who supported her and took on more child-rearing so that she could study. During her first year in the program, her house burned to the ground, and she and the family lost everything they had, but her Duke classmates hosted a dance to raise money and replace all the things they had lost in the fire.

Nichols was the first African American person to serve on the American Academy of Physician Assistants board. She established the AAPA Minority Affairs Committee. In an interview with the Rocky Mount in 1970, she stated

"The first year when I finish I want to spend working in the ghetto."

She collaborated with Dr. Charles Johnson, the first black physician, apart of Duke faculty, to secure funds and establish the first rural satellite health clinic in North Carolina and the country. As funding became scarce, she would move on to Lincoln Community Health Center, formerly known as Lincoln Hospital, which was the only hospital in Durham for blacks. She served there until she retired in 1995. May we be inspired by Mrs. Joyce's story and her persistence in advocating for minorities in the medical industry and addressing the health disparities that existed in the Durham community amongst blacks and the surrounding areas.

Some of her other accomplishments and work include:

Nichols helped found and served on the Board of Directors of the North Carolina Academy of Physician Assistants.

Preceptor and adjunct faculty member of the Department of Community and Family Medicine

Duke University PA Alumni Hall of fame in 2002 for her concerns for poor people and her advocacy skills.

Commissioner to the Durham Housing Authority winning many legal concessions for tenants.

Member of the Board of Directors of the Durham County Hospital Corporation and the Lincoln Community Health Center.

1991 Nancy Susan Reynolds Award for Advocacy

1996 she was named the AAPA Paragon “Humanitarian of the Year.”

Resources:

Shestak, Elizabeth (2012-08-27). "She Led Way Beyond Nursing to PA Work". The News and Observer. pp. B1. Retrieved 2020-05-14 – via Newspapers.com. and "Nichols". The News and Observer. 27 August 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

Sigler, Joe (1970-07-21). "Duke's First Woman Physician's Assistant Had One Stumbling Block - Her Sex". Rocky Mount Telegram. p. 7. Retrieved 2020-05-14– via Newspapers.com.

Carter, Reginald (August 2012). "Joyce Nichols, PA-C". Physician Assistant History Society. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

#BlackWomeninBullCity | Pauli Murray

““It has taken me almost a lifetime to discover that true emancipation lies in the acceptance of the whole past, in deriving strength from all my roots, in facing up to the degradation as well as the dignity of my ancestors.” Pauli Murray ”

I hope the stories that I've been sharing of women from Durham have been enlightening and insightful for those of you reading. As much as you may think that I have known these women my entire life, the reality is that I have not. I had never heard of any of them. I found myself somewhat disappointed that having been raised in Durham and also educated in the Durham Public School system, I never received a thorough education in Durham's history and the people and their impact aside from knowing about Black Wall Street. However, I'm grateful to possess the historical and intellectual curiosity about my history that inspired me to begin this journey of discovering more about my roots. This week I'm back with a brief post about an exceptional woman that I found in my readings, and her name is Pauli Murray. Ms. Murray was a poet, activist, attorney, professor of law, and the first African American woman to become an Episcopal priest. What I found so striking about her story is that Ms. Murray was not born in Durham but moved to what she had called a "frontier town" at the age of three from Baltimore in 1914. She grew up in her grandfather Fitzgerald's home on Carroll Street. She attended West End School, which she explicitly recalls being one of her earliest realizations that what they received as negro children was different from that of the white children. Stating that "it wasn't the hardships that hurt but rather the contrast between what we had and what the white children had.

“ I'll never forget West End School. It was a rickety old wooden built building with the paint peeling; I can see those scales now. You know how wood or shingles or paint blisters and I can see it. When there was a wind in a storm, you could just hear the wind blowing through that old building. I think that it was a two storey building, it might have been a three storey building, but anyway … And of course, the white kids school, a nice brick school sitting in a lawn surrounded by a fence. West End was up on a sort of clay, barren ground. There was no lawn whatsoever. It just sat on clay. The fact that I can remember this today and I can see that old school building there, no swings, nothing to play with when you went out …”

1926 Hillside High School

From an early age, she had a disdain for segregation, and all she wanted was to get away from it. Murray attended Hillside High School, formerly known as Hillside Park High School. She graduated from Hillside with a certificate of distinction. She would later attend Hunter College in NYC, although she had received a scholarship to Wilberforce University she did not want to attend any segregated schools.

“When I graduated from high school with honors, the Wilberforce Club got together and bestowed a scholarship upon me to go to Wilberforce and I turned it down.

…No more segregation for me. I was fifteen, but that I knew.”

Perhaps one of Pauli's most significant events was her 1938 campaign to enter into UNC-Chapel Hill's graduate program, where she was denied admission solely based on race. It received public attention, and she had sent off a letter to President Roosevelt, and although he did not respond, Eleanor Roosevelt did. The two would develop a long-standing relationship.

They sent me an application blank and they had written into the printed application blank, race and religion. This has been typed in so that it stands out apart from a normal form. I think I answered it but may have said, "But what difference does it make?" Obviously tongue in cheek. In due course, I got back a letter from Dr. Frank Graham, who was the then president of the University of North Carolina, saying, "I'm sorry, but the constitution and the laws of the state of North Carolina prohibit me from admitting one of your race to the law school.

This event was followed by Murray’s involvement to desegregate public transport, which resulted in her being arrested in March of 1940 on a bus ride from Washington to Durham and subsequently being convicted for resisting segregation on an interstate bus. Murray says:

They charged us with creating a disturbance, breaking the segregation law, violating the segregation law and creating a disturbance.

A year later, she would attend Howard University School of Law and later became a field secretary of the Workers Defense League concerning the case of Odell Waller, a black sharecropper convicted of first-degree murder of his white landlord by a white poll tax jury. She would also go on to help in a collaborative effort to form the Congress on Racial Equality. After working in the field of law for some time and serving her community in the fight for racial equality, she sought out a degree in law at Harvard, is that she had been awarded a fellowship, but they denied her entrance because of her sex. But it was actually at Howard that Murray says marked the beginning of her conscious feminism and awareness of sex and gender discrimination.

In 1956 Murray published Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family, a biography of her grandparents, and their struggle with racial prejudice and a poignant portrayal of her hometown of Durham. It’s important to note that Pauli identified her self as a civil libertarian and person who was committed to advancing human rights wherever she went. During her time in Accra, Ghana, while serving as a senior lecturer at the Law School. Out of her experience in Accra, came a book that she co-wrote entitled, The Constitution and Government of Ghana. When she returned, she would be appointed by President John F. Kennedy to his Committee on Civil and Political Rights. While Murray worked closely with several prominent black male civil rights leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Philip Randolph. She grew tired of the blatant dismissive attitude many of them had towards negro women and their role in advancing our rights in the fight for freedom. In 1963 she wrote to Randolph saying “been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grass-roots levels of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned in the national policy-making decisions.” Before she passed, Pauli Murray’s final accomplishment was In 1977, when she became the first African American woman to become an Episcopal priest.

Today you can see murals of Pauli Murray as part of the Face Up: Telling Stories of Community Life, a collaborative public art project in Durham, North Carolina. Artist, Brett Cook, led it.

One thing I’ve grown to admire about Pauli Murray through my research on her life’s work is her undeniable resiliency and persistence in the pursuit of her own freedom. She did not back down no matter what stood in her way. She was so progressive for the time in which she lived. Pauli Murray had truly emancipated her mind and was determined to not accept an inferior position in this world because of the color of her skin or the fact that she was a woman. If you’d like to read more about her or read her work please check out some of the resources below.

Thanks for reading and learning with me!

Love Light and Peace.

Sources:

Our Separate Ways by Christina Greene

Interview with Pauli Murray, February 13, 1976.

Interview G-0044. Southern Oral History Program Collection

https://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/G-0044/G-0044.html

https://paulimurrayproject.org/

Pauli Murray’s Writing’s:

“An American Credo.” Common Ground 5, no. 2 (1945): 22-24.

“And the Riots Came.” The Call, Friday, August 13 1943, 1; 4.

“A Blueprint for First Class Citizenship.” The Crisis 51 (1944): 358-59.

Dark Testament and Other Poems. Norwalk, CT: Silvermine, 1970.

Human Rights U.S.A.: 1948-1966. Cincinnati, Service Center, Board of Misions, Methodist Church, 1967.

“Negro Youth’s Dilemma.” Threshold, April 1942, 8-11.

“Negroes Are Fed Up.” Common Sense, August 1943, 274-76.

Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

“The Right to Equal Opportunity in Employment.” California Law Review 33 (1945): 388-433.

“Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy.” J.S.D., Yale University, 1965.

Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage. New York: Harper & Row, 1987.

States’ Laws on Race and Color. Cincinnati: Women’s Division of Christian Service, Board of Missions and Church Extension, Methodist Church, 1951.

“Three Thousand Miles on a Dime in Ten Days.” In Negro Anthology: 1931-1934, edited by Nancy Cunard, 90-93. London: Wishart and Co., 1934.

“Why Negro Girls Stay Single.” Negro Digest 5, no. 9 (1947): 4-8.

Murray, Pauli, and Henry Babcock. “An Alternative Weapon.” South Today, (Winter 1942-1943): 53-57.

Murray, Pauli, and Mary O. Eastwood. “Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title Vii.” George Washington Law Review 34, no. 2 (1965): 232-56.

Murray, Pauli, and Leslie Rubin. The Constitution and Government of Ghana. London: Sweet and Maxwell, 1964.

#BlackWomeninBullCity | Ersaline Williams & The Sojourners for Truth and Justice

This blog post was inspired by my desire to learn more about the role that black women have played in the fight for the liberation of black people everywhere from injustice. I've been able to spend more time reading more books, and I've rediscovered my love for historical literature on my people and our struggle, specifically, black women's historical writing. We can't continue fighting for justice while not reading books and literature based on the perspectives and experiences of black women. I was triggered by the story of our sister Toyin Salau who sexually assaulted and then murdered. There are many other countless stories of black women who have experienced sexual violence at the hands of men that we do and do not know. Furthermore, there have been SO many of us who have been survivors of sexual violence telling our stories but not even having the support of the black men who we defend and fight for every chance we get.

This devastates me.

I wanted to begin by gaining a firm understanding of how women from my hometown, Durham, North Carolina, also known as Bull City, organized for the sake of bringing justice to their communities. Durham was considered to be "capital of the black middle class" in the 1920s and garnered the praise of renowned leaders, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B Du Bois. It is the home of the largest black-owned financial institution in the country, North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. While many of Durham's black male elite's achievements are important to note, the efforts and organizing, accomplishments, challenges, and injustices faced by black women in the City of Durham have made been invisible and overlooked.

My purpose in writing this blog is to serve as an introduction to a longer-term project to begin to highlight and share more about the history of black women's work in Durham, to seek justice for themselves, their families, and their community from past to present. Much of what I will be sharing comes directly from books, publications, and media that covered the experiences of black women in Durham. When I share the information, I will ALWAYS attach the sources.

For today I wanted to highlight the story of Ersaline Williams.

http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn83045120/1952-07-12/ed-1/seq-1/

In 1952 Ersalene Williams, a black woman in Durham searching for work was asked by Thomas Wilbert Clark, a white man, to assist his wife with some household chores. She agreed, but when she arrived, Mr. Clarke's wife was nowhere in sight...

Mr. Clarke pounced on Ms. Williams without warning. When she rejected his "pawing", he offered her money for "immoral purposes" by the press. Ms. Williams, horrified, kicked and screamed, while Mr. Clark dragged her into the bedroom, tossed her on the bed, and got on top of her. During a "frantic struggle", she managed to free herself and escape. Soon after, Mr. Clark appeared at her home to apologize, explaining he had been drinking and could just forget about it. Ms. Williams refused, and Mr. Clark then returned with two white detectives hoping to intimidate her. His plan backfired, and Ms. Williams swore out a warrant for Mr. Clark's arrest. She then said, "Later on in the day, two other white men came to her home and offered me money to compromise. They stated that I would gain nothing because [Clark] would probably [not get more] than 30 days. During the time, Durham's traditional middle/upper-class black male leadership remained silent in the case of the attack on Ersalene Williams. Durham's weekly, The Carolina Times, denounced the black male elite for their silence. Durham's Sojourners for Truth and Justice, a local African American women's group rallied behind Ms. Ersaline in the fight for justice and truth.

The story and assault of Ersaline Williams were all too common for many black women in the south. This type of sexual and racialized violence has plagued our black women for centuries. There is still a struggle to protect black girls and women that shall remain as a priority in black liberation. Unfortunately, black women remain disproprotionately vulnerable to sexual abuse due to intersectionality, the systematic oppression that black women experience based upon the intersection of their race and gender. These institutionalized practices and policies prevent equitable enforcement. The "Strong Black Woman" stereotype, that focuses primarily on uplifting black women through their strength, perseverance, and survival and minimizes their emotional well-being, tenderness, and humanity further promotes silencing the pain of black women and girls.

According to the National Center on Violence Against Women in the Black Community (PDF, 772KB):

For every black woman who reports a rape, at least 15 black women do not report.

One in four black girls will be sexually abused before the age of 18.

One in five black women are survivors of rape.

Thirty-five percent of black women experienced some form of contact sexual violence during their lifetime.

Forty to sixty percent of black women report being subjected to coercive sexual contact by age 18.

Seventeen percent of black women experienced sexual violence other than rape by an intimate partner during their lifetime.

The Institute for Women's Policy Research reports that:

More than 20 percent of black women are raped during their lifetimes — a higher share than among women overall.

Black women were two and a half times more likely to be murdered by men than their white counterparts. And, more than 9 in 10 black female victims knew their killers.

Black women also experience significantly higher rates of psychological abuse — including humiliation, insults, name-calling, and coercive control — than do women overall.

You may ask yourself, What can I Do? Here are some suggestions to start with:

Become an informed ally. Learn about the relationship between colonialism and sexual violence. Read more books by black women scholars who are writing about the lived experiences of black women, including sexual abuse. #CiteBlackWomen is a good start.

Center black women in your advocacy. Contact elected officials. Ask them what they are doing specifically to improve the sexual violence experienced by black women. It may be helpful to explain how institutions contribute to gendered racism. Ask them to reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act.

Support local grassroots organizations that work on behalf of black women in your community. This may require you to do some research, talking with black women, and allowing them to tell you what they need.

Black women should not be forgotten survivors of sexual violence. It's 2020, and it is time that we begin to build capacity in local, regional, and national communities to create sustainable change and end sexual violence against black women everywhere. This story is symbolic of the legacy Durham's African American women have created in the fight for justice. It also highlights the importance of black women's community work and organizing in the Freedom Movement for black folks in America. I'm excited to continue to share more about the history of black women in Durham. If you have more information on Black women from Durham, NC, and would like me to highlight their stories as a part of the Black Women in Bull City project, please fill out the contact form on my website and Let's Connect!

Sources:

NC Newspapers: http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn83045120/1952-07-12/ed-1/seq-1/

NC Digital Heritage Center

Our Separate Ways by Christina Greene: https://www.amazon.com/Our-Separate-Ways-Movement-Carolina-ebook/dp/B001P82APY

https://www.apa.org/pi/about/newsletter/2020/02/black-women-sexual-assault